Introduction

Spring 2013. I was in my final semester of graduate school at the time. After reaching a 100-pound weight loss milestone just a couple years prior, I had adopted a fit lifestyle that included running 5 miles daily. One night in March, I noticed I was fairly winded very early in my run so I lowered the treadmill speed to a walking pace to try to catch my breath. Only I wasn’t catching my breath as I had expected and I suddenly felt myself getting lightheaded and a feeling that I was going to “shut off”. And then I did shut off.

When I came to, I was lying at the foot of the treadmill and the belt still running. I got a friction burn on my chest due to the treadmill belt pulling my shirt. A woman who was using a nearby elliptical machine rushed over to turn off the treadmill and asked if I was okay. I was in shock that I had apparently passed out and couldn’t answer her right away. I felt okay enough to get up so I walked to the entrance of the gym and sat in a char. As I was sitting, I began to feel waves of light-headedness and shortness of breath and palpitations in my chest. And then I got in my car and drove home. A few months later and after several more episodes of fainting and nearly fainting, I would be diagnosed with CPVT.

What is CPVT?

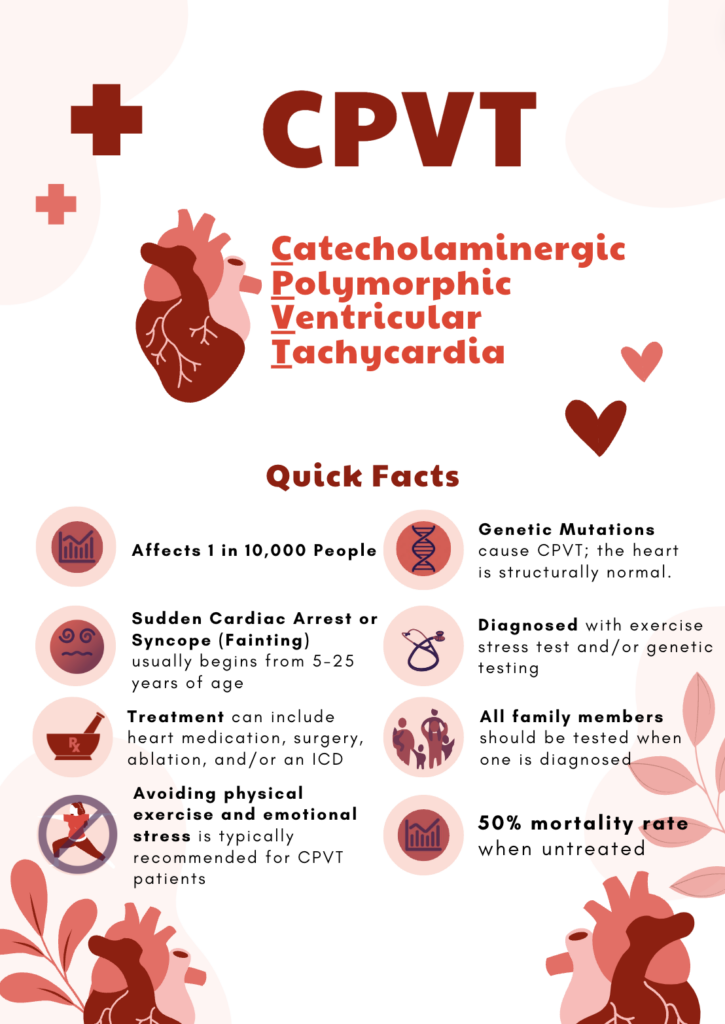

Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia (CPVT) is a rare heart condition that affects 1 in 10,000 people. CPVT causes irregular heart rhythms (arrhythmias) during physical activity or emotional stress. In simpler terms, imagine your heart as a drummer in a band that usually keeps a steady beat. But sometimes, when you're exercising or feeling very stressed or excited, this drummer starts to play an erratic rhythm that doesn't match the song. This is what happens in CPVT: the heart beats in an unusual and rapid rhythm that can lead to dizziness, fainting (syncope), and sudden death.

In essence, CPVT is a condition where the heart's electrical system, which usually controls your heart rate, doesn't respond well to the natural stress signals, causing the heart to beat very fast and in an uncoordinated way, especially during times when your body is under stress or during physical activity.

CPVT is caused by various genetic mutations. Mutations of the RYR2 and CASQ2 genes account for 1/3 of CPVT cases. Remaining cases are believed to be due to mutations that have not yet been identified.

Living with CPVT

There are good days and bad days when living with CPVT. For me, a good day is one where I do not experience any symptoms and bad days are where I experience symptoms and/or a shock. Sometimes bad days occur because I may have missed multiple doses of my heart medications. And sometimes cardiac events break through despite sticking to the medication. There are days where an arrhythmia may start out of the blue with no apparent stress trigger. Read the ICD shocks and Electrical Storms sections of this post for more examples of bad days.

In the first few years of my diagnosis, I would have a lots of short cardiac events, non-sustained ventricular tachycardia or NSVT, at all times of the day (before/during/after work). While my device didn’t need to shock me for many of these, I would still feel the symptoms that come with the arrhythmia – palpitations, shortness of breath and lightheadedness. For me experiencing the symptoms is worse than the shock because I have to wonder about whether I’m okay and safe in those moments.

I find myself being more aware of my surroundings. For example, when I enter buildings, I am mindful of where the nearest AEDs are (if there are any) and I wonder how long it might take someone to get bring an AED to me should I go into sudden cardiac arrest. As much as I love cardio workouts, I have an on/off relationship with the gym because exercise triggers arrhythmias. I have managed to land on a combination of heart medications that allows me to have a lot of symptom-free cardio workouts. I probably won’t be able to run 5 miles a day like I used to though.

In this post I’ll talk about the symptoms and tests that lead to my diagnosis, the various treatments I have tried, and some of the hurdles I encountered along the way.

My Diagnosis Story

Symptoms

My first sign was that something was wrong was when I lost consciousness on a treadmill. I passed out one more time in the gym about a month later. Up until this time in my life, I never had any indication that I might have a heart condition. Other signs that something was wrong was that I would get light-headed and short of breath throughout the day. I did not seek medical advice until about two months later after having another event in the gym where I felt very close to passing out again on the treadmill. I posted about it on Facebook and a friend of mine whose father is a cardiologist mentioned that my issue could be heart-related.

I needed to get some answers so I called a primary care physician and described what had been going on and they asked me to come by that same day at any time. That should have been a sign to me that my symptoms were very concerning to them, because walk-in appointments are fairly rare. When I got there, the doctor ordered a number of tests – bloodwork, electrocardiogram (ECG), and echocardiogram (EKG) and everything seemed just about normal. My bloodwork showed elevated troponin levels. The doctor asked if I was certain about the symptoms I was experiencing the past few months and I went over the details with her again. The doctor ordered an electroencephalogram (EEG) and also advised me to go to the Emergency Department (ED) and inform the staff that I had “elevated cardiac enzymes.”

I felt fine at the time, so I told her I would go to the ED later that week. I presented to the ED on a Friday after work and relayed the message about the elevated cardiac enzymes and explained the fainting spells. Aside from what I told them, I appeared healthy. I was admitted to the hospital seemingly based on the complaint of my symptoms and the elevated troponin levels in my bloodwork. No testing could be done because it was after business hours, so I got to spend the weekend repeating my story to doctors and nurses until Monday.

Side bar: Although I told the doctors and nurses that I do not consume drugs nor alcohol, they felt the need to do a toxicology screen because although I “looked healthy” they wanted to ensure I was not using drugs. Of course the toxicology screen did not detect any substances in my system. I can’t say for sure if the push for this testing was rooted in bias, but I’m lucky they didn’t discharge me as healthy as other has been done to other patients who had similar symptoms. Lakesha Benson’s son had similar symptoms and was discharged from the hospital when his toxicology screen yielded no results. He later died suddenly while playing basketball. Click here to read more about that experience.

Testing

Monday finally came and a slew of tests began. It seems they started with less invasive testing to assess whether my heart was structurally normal before considering more elaborate hypotheses. Further testing included a CT scan, a nuclear exercise stress test, another test where they injected epinephrine in my IV line for several minutes. Much of the testing was unremarkable (normal), except for the exercise stress test.

An exercise stress test is typically a patient on a treadmill while wearing a blood pressure cuff, oximeter, and 12 ECG leads to monitor heart rate and rhythm. Once the test starts, the treadmill speed and incline gradually increases at each minute and the blood pressure cuff inflates and deflates, until the patient asks to stop the test. I lasted pretty long on the treadmill since it was very similar to how I used the treadmill. Eventually I asked them to stop the test because I could no longer keep up, and while I was sitting down recovering (catching my breath) and I began to feel the same symptoms that I felt in the gym.

The doctors who were watching my heart rhythm live on the monitors asked how I was feeling. I explained that I felt “weird” like at the gym. One of the doctors mentioned that that what he was seeing is exactly what could cause me to faint and stated that I was lucky to still be alive after the two times I fainted in the gym. I was relieved that they finally got what they needed to believe I wasn’t making this up. Now we could now move forward with treatment.

Diagnosis and ICD

The doctors explained the results of the stress test to me and explained that I had CPVT. I remember being annoyed because they were using the full words instead of the abbreviation. It was all going in through one ear and out of the other. I was 23 years old hearing for the first time that I have a heart condition and I was being told that I need to have an ICD implanted in my chest. I simply couldn’t believe what I was hearing and I even refused the ICD initially. I wanted a second opinion. They recruited my mom to convince me otherwise. She told me about how my grandmother was in a very same predicament as me and had refused a pacemaker and how her doctor’s ordered indefinite bed rest for her. My grandmother passed away suddenly before I was born.

I eventually agreed to get the ICD although I truly didn’t want it. After I was discharged from the hospital, I continued to have episodes of dizziness and lightheadedness. I would feel symptoms onset while doing working in the office or driving and of course while exercising. I struggled in the early days of my diagnosis trying to cope with what this meant for my life. I still struggle with it sometimes. But at that time, I needed figure something out quickly because I intended to stick to my start date at the FBI, which was only 10 days away.

Medication 💊

With CPVT, a beta blocker is usually prescribed as well as an ion channel blocker. I am expected to take heart medication every day for the rest of my life. The medication tends to cause a fair amount of fatigue for myself and many other patients to the point that many of us find ourselves napping after a day of work or school. If medications aren’t effective at reducing symptoms, there are more invasive treatments that CPVT patients may consider, which I will talk about later in the post.

There is also a medication called Amiodarone that is effective at mitigating arrhythmias but it is also very toxic and can be really toxic for the thyroid and liver. In fact, the FDA indicates it should be used as a last resort. I was prescribed Amiodarone when my doctors could not get control of my symptoms, but I wasn’t given an exit strategy.

I had to advocate for myself and find a Cardiac Electrophysiologist who was willing to try something else, so I did. Now I am finally on a combination of medication that reduces my symptoms enough to allow me to safely exercise without triggering an arrhythmia.

ICD Shocks ⚡

My ICD is a first responder when I am having a cardiac event. It has certainly saved my life numerous times where it had to deliver shocks to bring my heart out of fibrillation. Some say that it feels like a horse kicking you in the chest. I’ve never been kicked in the chest by a horse so I can’t say that comparison is valid. I can say that shocks from my ICD were painless, but they also surprise me each time even though I always anticipate them. I yelp whenever my ICD fires and I also see a flash of light. Although, when I have received ICD shocks in public, no one seems to hear the yelp or notice. My ICD also attempts to terminate arrhythmias with anti-tachycardia pacing – which is a series of pulses that feel like a flutter in the chest – to avoid discharging a shock.

At first the shocks were cool, but after a while each one begins to have a psychological and emotional price. Shocks can lead to fear and anxiety around the behaviors or symptoms you experience at the time of the shocks. That fear can lead to the patient avoiding those behaviors altogether. Despite some of the negative effects of ICD shocks, I am grateful for them saving my life time and time again.

Electrical Storms 🌩️

There are various medical definitions for an electrical storm. The one I’ll go with is: 3 or more occurrences of ventricular tachycardia (VT) or ventricular fibrillation (VF) within a 24 hour period. On December 1, 2017 during rush hour on a Friday afternoon, I experienced an electrical storm. After I got home from work, I noticed I was experiencing waves of shortness of breath and light-headedness, and then I realized I was having cardiac events. I called my Doctor to let him know I wasn’t feeling well with the new medication and then called 9-1-1 since I started to have multiple ICD shocks.

For over a half hour, my heart kept going into VT/VF after my ICD appropriately delivered shock therapies to terminate the arrhythmias. It was a viscous cycle. I knew my ICD had about 9 years of life because I replaced my ICD the previous year. I didn’t know though if 9 years of battery life was enough juice to get me through this horrific loop. I accepted that I might very well die there waiting for Emergency Medical Services to arrive. I kept my cool and followed the advice of the 9-1-1 operator. I learned so much about my capacity for grace under fire in these moments. When doctors at the hospital interrogated my device, they found that my ICD had delivered 32 shocks for this electrical storm and the ICD would then have about 5 years of life remaining. I would then spend the week in the Cardiac ICU. The electrical storm was believed to be related to my transitioning to a different heart medication the day before.

Catheter Ablations

A catheter ablation is a procedure where radio-frequencies are used to destroy small amounts of tissue in the heart to hopefully prevent arrhythmia from reoccurring. The procedure is typically done under anesthesia. The two times I had the procedure done, the surgeon intentionally woke me up in the middle of the procedures. This is because it can be hard to reproduce the arrhythmia while you are under anesthesia and that was the case for me. If the arrhythmia cannot be reproduced during the ablation, EPs may believe this means the the ablation was successful and no more arrhythmias will occur. That was expressed to me after my first ablation, and I was told I could stop taking my heart medication, so I did. Eventually I began to have cardiac events which meant the ablation did not mitigate the issue. The second ablation also was not effective so I gave up on ablations.

Left Cardiac Sympathetic Denervation

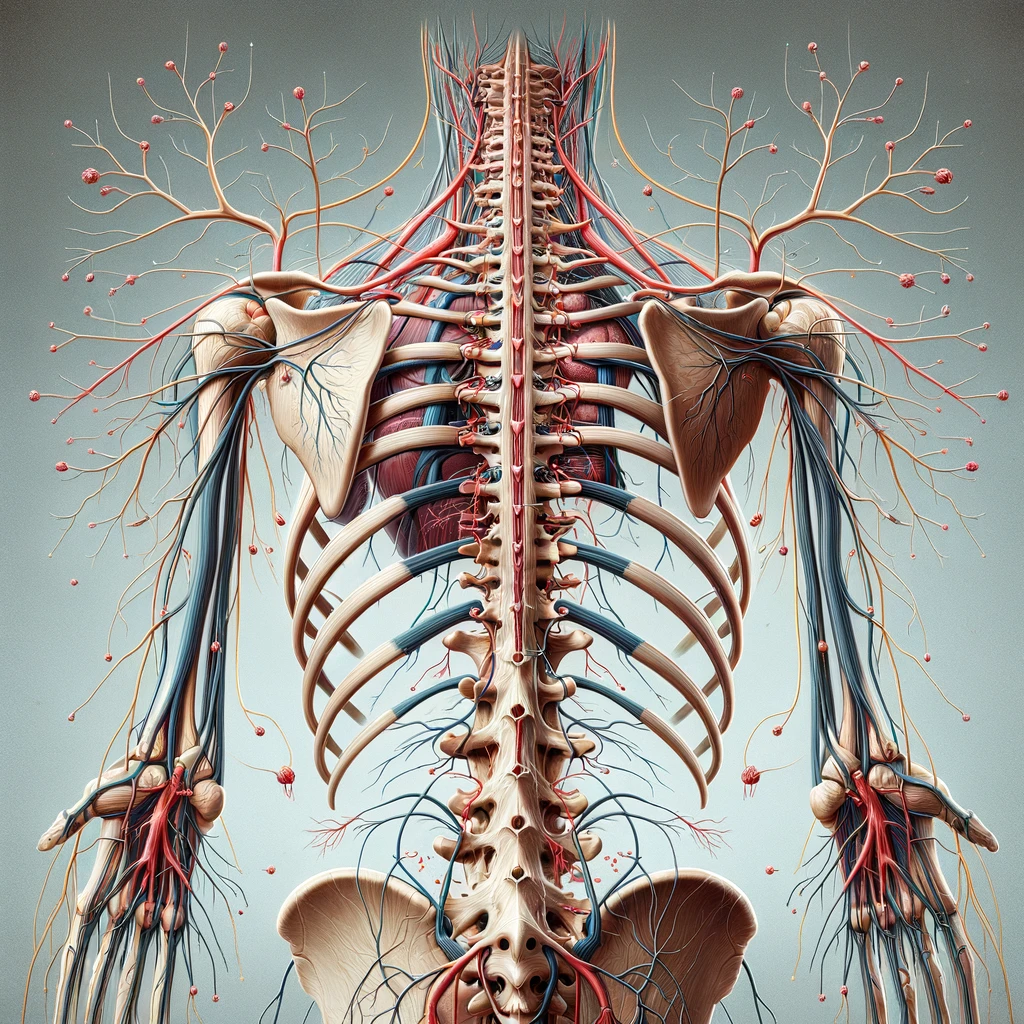

Medical research suggests that removing a certain part of the nerve chain that controls our stress hormones can help some CPVT patients live without symptoms. This surgery is called Left Cardiac Sympathetic Denervation (LCSD) or simply a "sympathectomy."

I had this surgery a number of years ago when I was still having a lot of bad days after exhausting all other treatments. LCSD didn't improve my quality of life, though it did change some things permanently – I can no longer sweat on the left side of my body, which leads to compensatory sweating on my right half. Because these nerves are important for how our body responds to stress and danger, the surgery can also change how we react to these situations. Some CPVT patients that I met in support groups have had worse luck with the procedure, most notably never-ending excruciating nerve pain. This risk is communicated to us (but downplayed) before the procedure, but we assume the risk in pursuit of relief.

Doctors

CPVT patients often establish care under cardiologists that specialize in Cardiac Electrophysiology. Having a care team that is both knowledgeable about CPVT and supportive is crucial for us, especially when the treatment plan is missing the mark. Throughout my journey Jan Nemec, M.D. (UPMC), Michael Ackerman, M.D. (Mayo Clinic), and Chad Robbins Brodt, M.D. (Stanford Healthcare) have been those doctors for me have been instrumental in helping me get the upper hand of my CPVT as well as getting off of toxic last-resort medication.

Knowing how to communicate my history with CPVT – the rationale for procedures and medication changes – was helpful when establishing care with new cardiac electrophysiologists (EPs). And more so, I found it’s important for patients and their families to maintain in-depth knowledge about the condition, their history with it, and treatment options. From my own experience and from speaking with other CPVT patients, there will be times where we have to advocate for ourselves, which sometimes requires speaking the same language as our Doctors and respectfully challenging them.

Conclusion

Thank you for making it this far! CPVT has taken SO MUCH from me over the years – time… money… energy… ambitions…. dreams… but I have learned so much from my experience about advocating for myself as a patient and not settling for mediocre care, resilience, perseverance, patience, empathy, listening, and grace under fire. It seems for now, though, that I finally have the upper hand of my CPVT and a decent quality of life. But there will be more bad days and many of us CPVT patients are just trying to cope and survive.

I want to give a shoutout to Brandy G Robinson whose Rare Disease story inspired me to post about my own.

Shanief is a seasoned cyber security professional, with over 8 years of diverse experience in enterprise intrusion detection, response and threat hunting.